If you’re a regular here at Agents of GUARD, you’ll have noticed that my last couple posts have been my musings on Wizard of the Coast’s latest edition of Dungeons & Dragons, simply named… well, Dungeons & Dragons. We on the outside call it D&D 5th Edition, it being the 5th iteration of the popular pen & paper roleplaying game. It’s just better that way… it eliminates any ambiguity.

Anyway, sometime ago in the Agents of GUARD Facebook chat, Agent Sarah asked if we had a “newb guide” to D&D. She had been going through my articles and found them a bit hard to follow. Rightly so, as they’re pretty jargon-y. For someone who doesn’t have D&D experience, it a downright foreign language. And surprisingly, we don’t have a D&D n00b guide on the site – shall we remedy that? We shall.

What is Dungeons & Dragons?

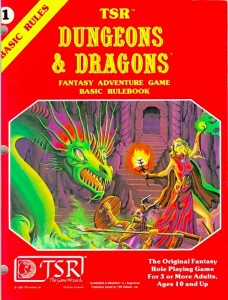

Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) is the grandpappy of all the pen-and-paper tabletop roleplaying games. Created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, D&D was a descendant of the historical wargaming rulesets that both Gygax and Arneson employed in their wargame campaigns. First published in 1974 by TSR, Inc., D&D has gone through several iterations and an ownership change (now owned by Wizards of the Coast, publishers of Magic: The Gathering), culminating in the current 5th edition.

Roleplaying game ya say? Whatsit that be?

My elevator pitch about role-playing games is this: Playing make-believe with rules.

Yup, that’s all D&D, and other roleplaying games are: playing group make-believe with a set of rules to make sure that the story created follows some kind of established reality, and doesn’t fly off the rails.

What it looks like IRL, especially to the uninitiated, is a group of people, usually sitting around a table telling stories and randomly rolling dice. Hopefully by the end of this, you’ll be able to decipher things a bit better.

In each roleplaying session, there are two types of participants, the Player(s) and the Dungeon Master, referred to colloquially as the DM. Together, these two groups of people endeavor to create a story that takes place in a world filled with fantastic beings, magical powers, epic heroism, dastardly plans, doomsday devices, and every kind of baddie you can dream up.

Each player takes control of a character in this make believe world. That player character, or PC for short, can do whatever they want in this the game world. If the player can come up with it, the PC can do it. Well, perhaps I should say, can attempt it. Like real life, any action a PC takes in the game world has repercussions. What those repercussions are and how they affect the story is up to, you guessed it, the DM.

The Dungeon Master

The Dungeon Master plays equal roles of storyteller and referee. It’s the Dungeon Master that sets the reality of the game world in which the PCs are immersed. The DM creates the backstory against which the players play make believe with their characters. His/hers is the final word on whether or not the PCs are successful at anything that occurs in game. They rule whether or not you’ve successfully hit an overhead dragon with your crossbow, or if your PC was able to mount their steed in time to escape a horde of undead, or if the Wizard in your group accidentally caught himself in his own fireball spell. In roleplaying systems other than D&D, the DM is usually referred to as a GM, or Game Master.

Of course, the DM can’t, on a whim, just decide whether or not these things happen. What fun is there in that? That gives no ownership of the story to the players. This is where the dice come in.

Dice

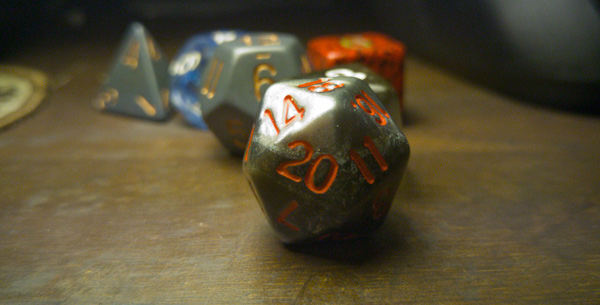

You may have seen a set of roleplaying dice before, a set of oddly shaped, too-many-sided little pieces of plastic or metal, with numbers on each side that stand in stark contrast to the six-sided, pip-marked die most people are accustomed to seeing. Sometimes, you’ll hear people refer to them as polyhedrals or polyhedral dice. They commonly range from the pyramid-shaped 4-sided die (d4) to the iconic isocahedral 20-sided die (d20). Rarer examples include the d2, d30, and d100.

What the dice do is account for any occurrence in the game world that has to do with chance, ability, or skill. Think of it like this – let’s say every morning, you run 5 miles. What are the chances that you’ll randomly run into someone you know during your run? I’m no actuary, but let’s assume you grew up in the neighborhood you’re running through, and there’s 16.66% chance that you’ll run into someone you know. How that would translate into the game world, is this:

The DM rolls a 6-sided die (d6), deciding that if the die lands on a 1, then you’ll encounter someone you know over the course of your run. This works out because, assuming perfectly random die, a d6 will land on a particular number, in this case 1, about 16.66% of the time.

We can take this further. How likely is it that you’ll actually complete your 5-mile run? Depending on certain factors, the Dungeon Master will give you the DC number, or Difficulty Class of a particular action, which indicates how difficult it will be for the character to successfully perform. Let’s say that you only recently decided to start running after a long sedentary period. The DM might tell you to roll a DC of 17, stating, “Ok, I’ll say you complete your run if you can roll over a 17 on a d20.” This gives you a 15% chance of success. If, however, you’re a seasoned runner, with a couple of 10ks under your belt, the DM might say, “Ok you complete your run successfully on a 3 or over,” for a success rate of 85%. This isn’t exactly how it works in-game, but it illustrates the point I’m making.

Most of these chance rules are outlined by the D&D Rule Books, but can also be according to DM discretion.

The dice are also used to decide things such as whether or not a player is able to intimidate a castle guard, or successfully hit an opponent with their battle axe, or how much damage that axe swing causes if landed.

Gameplay Example

Now that we’re nearing the end of the first part of this primer, let me give you an example of some gameplay:

Dungeon Master (DM): You walk into a the Lonely Pines Tavern. The first thing you notice is that it’s very, very busy. It’s got a good cross-section of the populace as patrons, but there are definitely more workers and peasants than merchants and nobles. Roll a perception check, DC 16.

Greg (rolling dice): 12.

Daisy: 8.

Mikhail: 19.

Jesse: 16.

DM: Both Mikhail and Jesse notice that amongst the revelry, there is a figure in the back of the Tavern, sitting oddly still. His cloak is drawn over the top half of his face, and he’s smoking a long, corn-cob pipe. Unlike everyone else around him, he’s not drinking anything.

Mikhail: I tell the others what I notice, and I make a bee-line toward this mysterious figure.

DM (rolling dice): He notices you, stands, and half-draws a previously unseen dagger from his left sleeve.

Mikhail: Whoa friend, I mean no harm, it’s just that I can recognize strangers to a place when I see them. I too, am new to these parts and would enjoy like company.

DM: Role a Persuasion check.

Mikhail (rolling): Aw, 9.

DM: With all your modifiers?

Mikhail: Yep.

DM: The figure is unconvinced by your words, he fully draws his dagger, and throws back his hood to reveal pointy ears and a gnarled face with a scar across his left eye.

Hopefully, that made more sense than it would have before you read this part of the primer. Tune in on the following weeks, where we’ll continue to demystify D&D by explaining player characters, race, class, and combat mechanics, as well as follow the continuing adventures of Mikhail, Jesse, Daisy, and Greg!